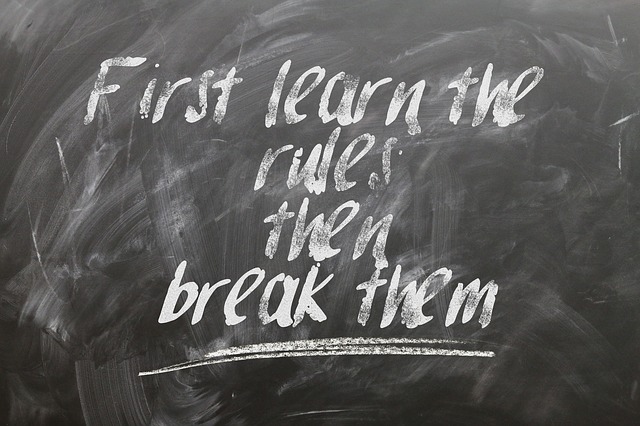

Do You Know Which Writing Rules to Break and When It’s Okay to Break Them?

Writing instructors and editors often stress certain rules for improving one’s writing and selling manuscripts to publishers and book/magazine buyers.

Some of these rules – like the admonition to “show don’t tell” – are so deeply engrained in writers’ advice arsenals that they have become clichés.

But while these rules are valuable guidelines, it’s important to remember that they don’t apply all the time.

In other words, it’s okay, and even desirable, to sometimes break these rules.

You just need. to know which writing rules to break and when to break them.

Here are three such rules:

1. Show, Don’t Tell.

Telling a reader something basically summarizes and draws conclusions for him or her.

For example, “Jimmy was tired because he was sick” or “Jamie has a beautiful face” tell the reader what the author concluded about these story characters.

In contrast, showing gives details that allow the reader to experience the scene and draw his or her own conclusions.

This draws the reader directly into the story.

“Jimmy slumped in his chair and struggled to keep his head upright as sweat poured off his face” shows, rather than tells, the reader that Jimmy was tired and probably sick.

In the second example, using the vague word “beautiful” expresses the author’s opinion of Jamie’s face, but since “beautiful” means different things to different people, it doesn’t reveal a whole lot.

In contrast, “The first things Matt noticed about Jamie were her creamy complexion, blue eyes, and wavy brown hair that framed her heart-shaped face” shows the reader what Jamie looks like and also shows Matt’s reaction to looking at her.

But while showing is important, sometimes writers get carried away with trying to show rather than tell the reader about every bit of minutiae in a story.

This can be overbearing and may not allow the story to move forward.

Deciding when and when not to do this can be tricky, but overall, if telling or summarizing helps move the story along or facilitates a transition to the next scene, it’s probably best to tell.

In the above example, it would be desirable to show Jimmy slumped in his chair, but once the reader has been drawn into the scene, it would be fine to summarize what happened next, as in “Tammy gasped when she entered the room and saw Jimmy.

She called 911, and the couple spent the rest of the afternoon in the hospital emergency room after paramedics transported them there.”

2. Don’t use adjectives and adverbs.

This is good advice… sometimes.

I think a better way of stating this rule is “use adjectives and adverbs sparingly.”

The problem is that many writers overuse vague descriptive words while trying to describe characters, things, or events in a story, and this adds unnecessary clutter without revealing much about what is being described.

One way to avoid this is to use vivid, specific words instead of vague, general terms like beautiful, good, bad, very, big, little, came, went, a building, a chair, a dog.

For example, consider the sentence “The medium-sized dog went into the big forest.”

Does this sentence really show you what’s happening and entice you to keep reading to find out what happens next?

Probably not.

Like I did, you probably found it uninteresting.

But using vivid, specific words and changing it to “The beagle dashed into the dense woods” lures me into the scene and makes me want to find out why this dog dashed into the woods and where he is going.

Using the specific noun “beagle” eliminated the need for the vague adjective “medium-sized,” but I did substitute the specific adjective “dense” for the vague “big” because “dense” helped paint the picture.

So it’s not necessary to completely banish adjectives and adverbs from your writing; just remember to use them appropriately to truly enhance your writing.

3. Don’t end a sentence with a preposition.

This is usually a good rule to follow, unless rearranging the sentence makes it really awkward.

For instance, “This is what I have spent years working for” ends with the preposition “for,” but moving the preposition to the middle of the sentence makes it sound awkward and contrived: “This is for what I have spent years working.”

Technically, the latter is grammatically correct, but most writers and editors would leave the sentence as originally stated because it is less awkward.

Another one that I would not change is “I need someone to lean on,” since the grammatically correct “I need someone on whom to lean” sounds awkward and contrived.

As with the other rules, it’s important to evaluate the pros and cons before deciding whether or not to break these dictums.

About Melissa Abramovitz

Melissa Abramovitz is an award-winning author/freelance writer who specializes in writing educational nonfiction books and magazine articles for all age groups, from preschoolers through adults.

Melissa Abramovitz is an award-winning author/freelance writer who specializes in writing educational nonfiction books and magazine articles for all age groups, from preschoolers through adults.

She has published hundreds of magazine articles and more than 50 educational books for children and teenagers.

She also does freelance editing and critiquing and writes short stories, poems, and picture books, and is the author of the acclaimed book for writers, A Treasure Trove of Opportunity: How to Write and Sell Articles for Children’s Magazines.

Melissa graduated summa cum laude from the University of California, San Diego with a degree in psychology and is also a graduate of The Institute of Children’s Literature.

She is a member of SCBWI.

Visit her website at www.melissaabramovitz.com

Learn how to publish children’s books with Children’s Kindle.

Note: This post may contain some affiliate links for your convenience (which means if you make a purchase after clicking a link I will earn a small commission but it won’t cost you a penny more)! Read my full disclosure and privacy policies...